Measuring NAND Longevity

No secret that NAND/Flash/SSD drives are fundamentally different to their spinning cousins. Yet given the relative lack of high-visibility maturity of NAND technologies within the enterprise, adoption of standards has yet to proliferate. Specifically around the determination of failure rate.

When we start looking at availability of mechanical drives or most components inside a server, we first refer to the MTBF.

The consumer-grade disks are generally rated at several thousand hours, whereas enterprise-grade drives typically see 1.3million+ hours of operation.

Due to the differences between spinning and SSD disk, it isn’t always appropriate to use MTBF as a measurement of the drives availability.

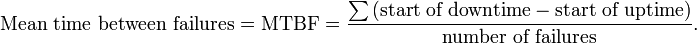

The NAND memory cell within the SSD doesn’t act in the same fashion as a spinning-disk block-abstraction. It must first be erased, prior to a write being carried out; unlike the spinning medium where a simple overwrite is possible.

The bits within a NAND cell are registered by electrons moving through a membrane/tunnel-oxide. It is responsible for keeping those electrons in check.

Gradually, over many program/erase operations the oxide starts to wear out. It is this event that should be avoided, as it will slowly start to cause single-bit errors, and cell locations that expect a 0 will be met with a friendly 1.

For this reason, the Flash Transformation Layer, responsible for all the internals of NAND management & carries out wear-leveling operations which evenly spread the load across hopefully all NAND cells.

Whilst looking at SSDs, there are SLC, MLC, and recently eMLC based flash memory. Difference being the amount of bits that are stored in the individual NAND cells. SLC has a single, whilst MLC/eMLC store two bits. In a lot of cases they’re actually exactly the same physical die, and what separates SLC from MLC/eMLC is the aforementioned FTL, amount of reserved space for the load balancing, and capability of the onboard ECC. This results in tunnel oxide in an SLC-rated drive having a typical life of around 100,000 program/erase cycles and 10,000 for MLC.

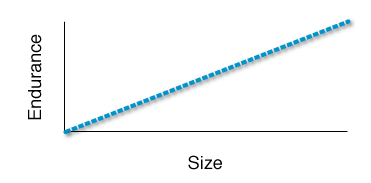

Now that you can see, that -most- of the wear on the drive occurs during cells actually being written to, and not idle time, given lack of moving components. With nothing changing, the larger the drive coupled with better FLT, the longer the drive will endure.

The reality check comes in the form of manufacturing processes, and as AnandTech points out, with the reduction in die size, results in extra sensitivity required to read each bit - there’s an inevitable hit in individual endurance of the cells. Yet the performance has been clearly increasing with each generation of die-size reduction, which is a result of the gain achieved in the controller power and thus any ECC coupled with greater reserved capacity on the disk has a net effect of - higher performance, and total better longevity.

NAND Endurance

Instead of looking at a mechanical, time-driven metric, the best way to calculate endurance of the drive is stress the oxide tunnel, and see how many times it can be trespassed, which translates to the amount of bits that can be written.

A standard that only several manufacturers have started to adopt is the JESD218 which gives an Endurance Rating in Terabytes Written (TBW). It also nicely classes client vs enterprise workloads where something as simple as the Power on state is measured (among others… see references).

Client

- 40ºC

- 8hrs/day

Enterprise

- 55ºC

- 24hrs/day

based on a use scenario in which the SSDs are actively used for some period of time during which the SSDs are written to their endurance ratings

Most importantly the standard is not using just time as a function by which to measure, but the actual endurance level. Therefore when you see a 20PB “TBW Enterprise” rating on a drive, you can quickly determine that the endurance of the drive over a 5 year period offers an ability to write 11 Terabytes per day [20*1024/(5*365)].

Next time you’re picking a drive, be weary of the correct metric being used to show you how long the unit will actually last. Knowing that each application is different, with its own workload profile - you will be able to easily figure out how long the said drive will last.